Emotional Regulation: Scientifically Proven Skills

Emotional regulation isn't about your personality.

It's actually about whether you've learned the right skills and strategies for managing your emotions.

The Science of Emotional Regulation: Learnable Skills That Change Everything

We often think that our personality is intricately linked with how we manage our emotions.

In some ways, this makes sense. The manifestation of our personality involves how emotionally regulated we are and what we do with our emotions. That's what other people see, and it might be how they perceive us.

But here's the key:

these are not inherent traits .

These are learnable skills .

And improving how you regulate your emotions can dramatically improve your satisfaction in life.

Today I'm going to share evidence-based scientific research that demonstrates that learnable skills help with emotional regulation.

Emotional Regulation Is Tied to How We Integrate These Skills

Emotional regulation is not about any single skill. It's about a collection of learnable skills that work together.

The magic of emotional regulation is actually in the integration of this set of skills.

I'm going to walk you through the cognitive, behavioral, and physiological skills that work most effectively when integrated and applied at the right time. Timing and application are key because research has demonstrated that proactively using these skills is the most effective approach. This means using them ahead of time, not after you're already in an overblown emotional state.

Cognitive Skills for Emotional Regulation

Two of the most impactful cognitive skills for emotional regulation are: Cognitive Reappraisal and Affect Labeling.

Cognitive Reappraisal: Changing How You Think About Something

I'm sure you've heard that how you think about things causes your emotions. I actually don't think that is completely true. However, how we think definitely influences our emotions. I know it's not always easy to change how we think, but that's why this is a skill. It requires practice and exploration.

**Examples of cognitive reappraisal:**

You did terribly on an exam. Instead of seeing that as a sign of your failure—that you are a total failure—you can see it as a signal. You might need to change your study habits. You might need to speak with the professor. There might be strategies that need to be employed to help you improve your performance. You could see it as information rather than a pervasive condemnation of your abilities.

The same principle applies if a job interview goes badly or a date goes badly. Instead of thinking "I'm a loser, I'm never going to find a good job, I'm never going to find somebody to date," you could think, "This is about finding a fit for me. Let me see what I can learn within each situation."

Now, I know it's not easy to make these changes. But scientifically conducted research has shown that cognitive reappraisal can lower the intensity of the emotion you're feeling. It can also change the expression so that you express less of that emotion on your face and publicly. And it does this without the backlash of simply suppressing emotions.

Suppressing emotions has been demonstrated in this same research to actually activate your physiology and exacerbate your emotional response.

One reason this isn't easy—and this isn't always discussed—is that we learn negative core beliefs about ourselves when we are very young. These come from dysfunctional family situations, from traumas, and from difficult situations we experience. Those negative core beliefs get ingrained so deeply that we believe they're truths. We don't see them as cognitions or as ways that we're thinking about ourselves. We see them as who we really are.

I do offer a free PDF called Transform Your Negative Core Belief. It helps you identify what your core negative belief is which underlies your cognitive distortions. It also provides you with techniques to begin overturning that core negative belief.

Affect Labeling: Naming Your Emotions

Research shows that affect labeling is extremely effective.

If you are feeling really upset, name it. Say it out loud if you can. "I feel very angry right now." "I feel really sad." "I feel super confused."

Labeling your emotions brings in your prefrontal cortex in a way that communicates with your amygdala. Your amygdala controls your fight, flight, freeze response. This prefrontal cortex engagement has been shown with FMRI studies to calm down your amygdala. ( This blog explains this ).

Both of these cognitive techniques work because they stimulate your frontal lobe which controls your executive functioning. This is the part of your brain that can begin to think about solutions to the problems you're facing instead of simply being in that reactive space of the fight, flight and freeze response.

Behavioral Techniques for Emotional Regulation

Now let's talk about behavioral techniques. In the behavioral area, I want to discuss **situation modification** and **where you place your attention**.

Situation Modification: Changing What You Can

Situation modification basically means asking: is there something about the upsetting situation that you can change or modify?

**Examples of situation modification**

For example, if you know you have to have a really difficult conversation with someone—a family member or a boss—make sure you're choosing a time when you're well rested and when you've had something to eat. You don't want to be too hungry. How can you modify the situation so it can go as well as possible?

Situation modification can also involve preparing some responses you might want to say or creating guidelines for yourself. If there are family members you want to stay in touch with, but they drink way too much, you can decide to meet them for breakfast or lunch instead. You can stop meeting them for dinner. You can stop calling them after four in the afternoon. All of these would be steps you can take to modify difficult situations.

It's interesting because some research shows that **cognitive reappraisal is not very effective if it's actually a situation you could modify**. Thinking about the situation differently with a relative who drinks too much may not be helpful if you could actually change something about the situation. You can't change their drinking, but you can talk to them at a different time of day. That's more effective than trying to talk yourself out of being upset when you talk to them and they're intoxicated.

Attentional Deployment: Where You Place Your Attention

The other behavioral technique is called attentional deployment. It basically means: where do you place your attention?

Let's talk about a really upsetting family event you're attending. There are certain people who argue politics and you just can't stand it. Figure out how to put your attention elsewhere. You can have a plan ahead of time if you know you're going into a situation that tends to get your emotions out of control. Make a decision to pay attention to the kids who are there, or do the dishes, or decide you're going to pay more attention to helping serve the food rather than getting involved in long discussions.

Where we place our attention is very powerful.

This ties into the third area of physiology because sometimes paying attention to the exact present moment is super helpful. Very often the things that are really upsetting to us are tied to things we are projecting into the future or ruminating about from the past.

But often right here, right now—take a deep breath—right here, right now is okay. I'm not talking about this being in the middle of family chaos or work chaos, but often we can find spaces even within those situations. We can take a moment, take a deep breath, and place our attention perhaps on a handful of the good things that are happening. We can appreciate something about the moment rather than getting stuck in projections or going over and over the past.

Attentional deployment, as you can tell, brings in the cognitive piece as well as the physiology of being in the moment.

Physiologically Calming Techniques

Two effective physiologically calming techniques are grounding techniques and "savoring the senses."

Grounding Techniques

Many people find that grounding techniques are more helpful than breathing techniques. I think once you practice grounding techniques, you will develop a greater capacity to focus on the breath and bring in breathing techniques. Both are really helpful.

Grounding techniques are about utilizing your senses to enhance your awareness of the present moment.

Grounding techniques could involve stamping your feet on the floor and really feeling the floor. You could try it right now. If you're feeling very agitated, you can stamp quickly. If you're not agitated, just roll your foot on the floor and feel that sensation. **

The more attention you can bring to that grounding technique, the more it will actually change your body chemicals and physiology. (Here's a video on Grounding Techniques ).

Savoring the Senses

This is actually a specific grounding technique, but I thought it was worth highlighting.

You can pick one sense—let's say the sense of smell. I know people who carry an essential oil that has a smell they find centering and grounding. Or you could use a cup of herbal tea. Pick something that has a smell that is comforting to you, and then really take a moment to breathe it in. Really expand the impact of that sense.

One of my favorite senses to use is hearing. It almost doesn't matter what you're hearing, and you can do this anytime, anywhere. You can do it right now. Just take a moment to listen without judgment, without judging the sounds. Don't think "Oh, I like that one. I don't like that one."

J ust listen to what the sound sounds like.

Then take a moment and see what's the furthest away sound you can hear.

Now what's the closest sound you can hear?

As you do this, notice physically if anything is shifting for you.

The Magic Is in Integration and Timing

As I said, "the magic of these techniques is in their integration."

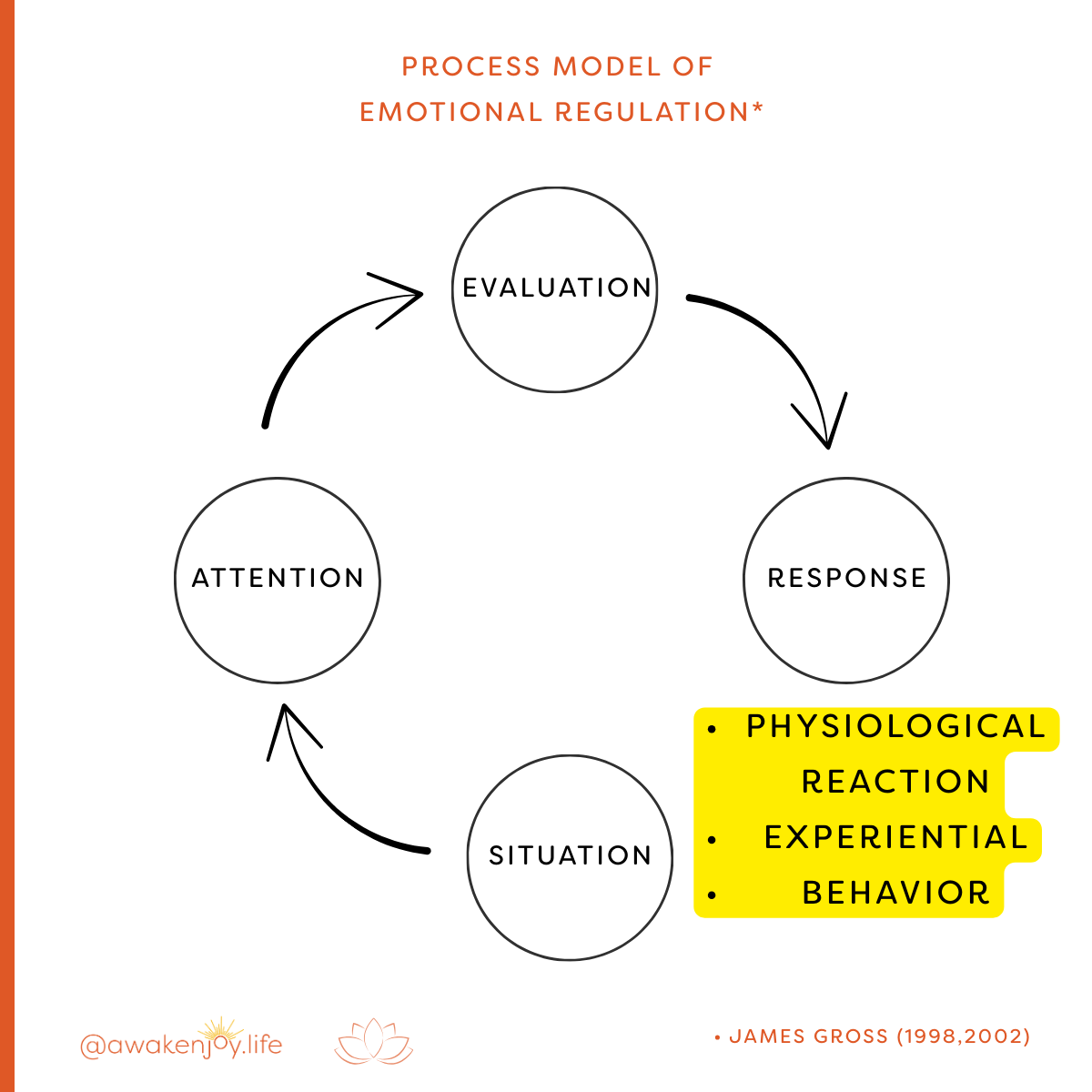

To talk about this, I'm going to use the process model of emotions (which I discussed in more detail in last week's

video and

blog ).

This model starts with a situation. Within that situation, there's what you pay attention to. Then there's your evaluation, your cognitive process—what you are thinking about what you've paid attention to in that situation. That's what develops your emotional response.

Your emotional response has a physiological reaction in the body (physical reaction). It has an experiential component (what emotion you are feeling), and it's tied to a behavior. This includes what you're showing on your face to the world as well as what you're doing. Then that emotional response feeds back into the situation.

Early Intervention Is Most Effective

In terms of regulating what emotions are going to come out of all of this, the earlier you can use some of these strategies, the better.

For example, people usually try to bring in physiologically calming techniques after they've had their full-blown emotional response. This has been proven not to be effective. If it is effective, it often has a cost in terms of tying it to that suppression of emotion, which has many other negative impacts. It also takes a lot of energy to calm yourself down once you've had this full-blown response.

Utilizing some of those physiological techniques before you get into a potentially upsetting situation is much more effective.

I also recommend that people practice the physiologically relaxing techniques on a regular basis. Don't tie them to any situation. Do diaphragmatic breathing three times a day, every day for five minutes at a time. If you practice it—remember these are skills that take practice and learning—it becomes much more accessible to you. Then you can also bring it in when you're in the middle of the situation.

If you bring it in before the situation, and then again during the situation, it will help you adjust your attention. This then helps you do the cognitive reappraisal, and it will help you deal with your emotions before they're full blown.

We can

also

bring in the cognitive reappraisal

before the situation begins. Before

we go to take that exam, before we go to the job interview, before we go to the upsetting family dinner, we can begin to utilize cognitive reappraisal.

And we can combine that cognitive reappraisal with the physiologically calming techniques and deep breathing.

This will help you choose more impactful behaviors, behaviors that will be more effective for what you want to achieve in the long run.

What About Trauma Triggers?

You might be thinking, "You're not talking about trauma triggers! I get triggered before I know any of this is even going on!"

That's true for many people who have emotional dysregulation difficulties. Sometimes something can be triggered before we're even consciously aware of it.

Sometimes our trauma triggers or emotional triggers go off as we're approaching a situation that we know will be difficult. But sometimes it could just be a smell or a sound, and all of a sudden we're in that physiological state and we don't know why.

I am going to do an entire video on emotional triggers and emotional regulation, however here are some quick suggestions:

The moment you are able to notice that you have gone into a physiologically aroused state of panic, bring in those grounding techniques that you hopefully practice every day on a regular basis. Move away from thoughts like "Why did I get triggered? What is wrong with me? I'll never get over this." All of those thoughts will contribute to escalating the emotional response you're having to the trigger.

The more you can just bring things back to the moment, the better. Figure out how to breathe, ground yourself, feel your feet on the floor, and notice what you're hearing.

Begin to practice bringing that in right away without all the thoughts that will complicate that process.

If you have specific questions or comments, please post them here or post them on

today's video. See you next week!

Blog Author: Barbara Heffernan, LCSW, MBA. Barbara is a licensed psychotherapist and specialist in anxiety, trauma, and healthy boundaries. She had a private practice in Connecticut for twenty years before starting her popular YouTube channel designed to help people around the world live a more joyful life. Barbara has a BA from Yale University, an MBA from Columbia University and an MSW from SCSU. More info on Barbara can be found on her bio page.

Share this with someone who can benefit from this blog!